Over the past year, catastrophic wildfires have wreaked havoc on the Western United States. These large-scale forest fires are a danger to society and the land, threatening lives, homes, and the entire forest ecosystem.

Despite popular belief, high-intensity wildfires are not a new phenomenon. Catastrophic fires did occur on particular landscapes before we began to suppress wildfires so freely. However, the current rate of occurrence for catastrophic fires is unprecedented and unsustainable.

For most citizens - those who haven’t been directly impacted by the destruction - once the smoke clears and the sky is blue again, things tend to go back to normal, and fire season is forgotten. However, the forest ecosystem doesn’t forget as quickly. Catastrophic forest fires can have long-term, negative effects on soil, air, water quality, and wildlife habitat.

Air Quality and Carbon Emissions

While smoke and air quality are top of mind for people during fire season, these temporary health effects may be the least of our concerns. Wildfires put out carbon and aerosol emissions that are detrimental to the ozone layer.

According to NASA, “September 2020 data from the Global Fire Emissions Database show that California wildfires in 2020 generated more than 91 million metric tons of carbon dioxide. That’s roughly 30 million metric tons more carbon dioxide emissions than the state emits annually from power production.”

This is problematic for two reasons, the first being that this increase in carbon dioxide emissions can negatively affect our climate, water quality, and air quality. Additionally, forests are one of our largest natural carbon sinks, capturing and storing carbon until the trees are burned or left to rot. With an increase in catastrophic wildfires, so many forests are being destroyed, eliminating their ability to sequester atmospheric carbon for many years or even decades.

Water Quality

According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), “approximately 80% of the freshwater resources in the U.S. originate on forested land, and more than 3,400 public drinking water systems are located in watersheds containing national forest lands.” With so much of our freshwater originating on forest land, it is essential that we do everything we can to try to protect these water sources, especially when it comes to wildfires.

Large catastrophic forest fires can have significant long-term effects on water quality. Ash and sediment can contaminate water sources, elevating nitrogen and carbon levels which can last for over a decade after the fire has been put out. This additional sediment can cause an increase in treatment cost and minimize reservoir capacity. Wildfires can also increase the runoff caused by a lack of vegetation and a change in soil composition, altering stream habitat and causing migration or die-off in aquatic species.

Soil Quality

Fires can also affect soil quality throughout forested landscapes. According to D.G Neary, Ph.D. in An Overview of Fire Effects on Soils, "The effects of fire on soils are a function of the amount of heat released from combusting biomass – the fire intensity – and the duration of combustion." This means that not all high-severity fires will have an extreme impact on soils if they don't last as long, while long lasting, low-intensity fires can significantly impact soil quality.

Neary goes on to explain that the "Physical impacts of fire on soil include breakdown in soil structure, reduced moisture retention and capacity, and development of water repellency, all of which increase susceptibility to erosion."

Habitat and Wildlife

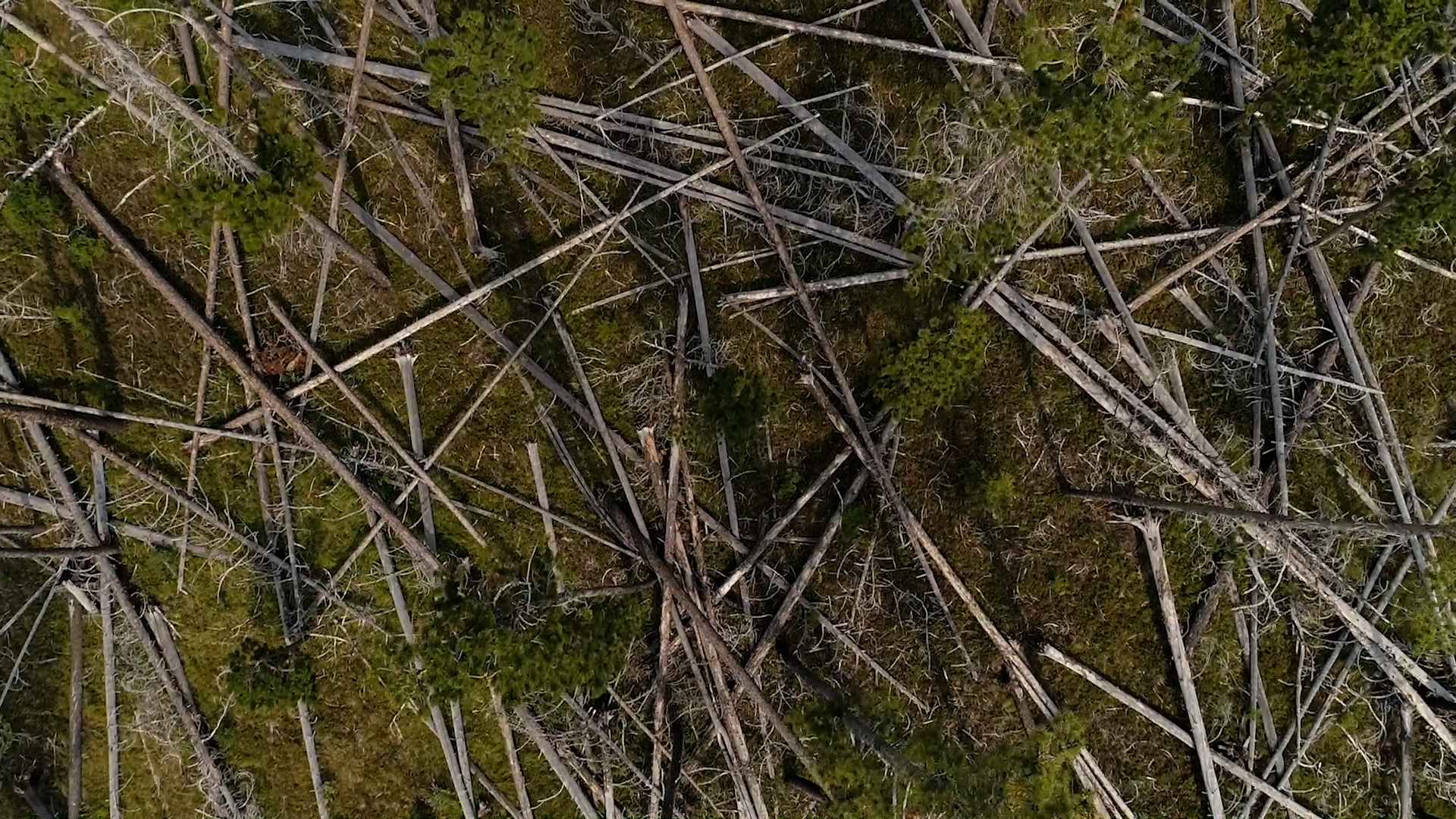

While low and mixed-severity fires can positively affect wildlife, encouraging regeneration and creating a habitat full of wildlife snags, high-intensity fires are a completely different beast. It is difficult to understand exactly how fire affects wildlife during these events; however, we do have an understanding of how different species behave after fires.

Large-scale forest fires tend to burn at such high temperatures that they destroy everything in their path. This completely alters the forest landscape, changing wildlife habitat and displacing species for long periods. According to the Bird Conservancy of the Rockies:

“Studies show that multiple species, from woodpeckers to spotted owls, will avoid severely burned habitats if they cover a large area, but not if they occur in smaller patches next to low-severity or unburned areas. High-severity fire can open the canopy and help plants grow on the forest floor, increasing availability for food for herbivores, and in turn their prey, but these species also require patches of forest for cover.”

This means that low-intensity fires or even mixed-intensity fires can be beneficial to promote habitat regeneration and therefore help wildlife thrive.

“Wildlife can respond positively to high-severity fire when it is intermixed with low severity fire, a pattern referred to as mixed-severity fire. This conclusion harkens back to the mosaic nature of historical forests. Vast expanses of uniform, unvarying forests are neither natural nor beneficial, whether unburned or severely burned.”

Forest Management’s Role

Although catastrophic wildfires aren’t a new phenomenon, the rate and scale of these recent fires should not be taken lightly. An overload of fuel has made these types of fires extremely difficult to fight and contain.

We are past the point of no interference. Humans have been interfering for years by suppressing fires and urbanizing wooded areas. This means that treatment is now necessary to ensure the safety of these first responders and the wildland-urban interface.

Forest management techniques such as mechanical thinning and prescribed burns are excellent ways to provide fuel breaks and to mimic the nature of low-intensity or mixed-intensity fires. This helps clean up stands, promote regeneration, and avoid high-severity wildfires.